Sandro Barni1*, Carlo Aschele2, Livio Blasi3, Monica Giordano4, Cinzia Ortega5, Graziella Pinotti6, Fabrizio Artioli7, Luisa Fioretto8, Bruno Daniele9, Giuseppe Aprile10, Rosa Rita Silva11, Vincenzo Montesarchio12, Alberto Scanni13, Paolo Tralongo14, Luigi Cavanna15

1Emeritus Medical Oncology, ASST BG Ovest Treviglio Hospital Bergamo. ORCID iD: https//ordid.org/0000-0002-7633-0378

2Department of Medical Oncology Sant’Andrea Hospital - La Spezia.

3Medical Oncology (ARNAS)-Civico, Palermo.

4Department of Oncology Sant’Anna Hospital , ASST-Lariana, Como

5Department of Oncology, San Lazzaro Hospital, Azienda sanitaria locale CN2, Alba - Alba-Bra.

6Medical Oncology - Varese

7Oncological Day Hospital Suzzara Hospital (Mantova)

8Department of Oncology Azienda USL Toscana Centro, Firenze

9Department of Oncology, Ospedale del Mare, ASL Napoli 1 Centro, Napoli.

10Department of Clinical Oncology, San Bortolo Hospital Azienda ULSS8 Berica, Vicenza

11Department of Oncology ASUR Marche, Area Vasta 2, Fabriano

12Medical Oncology Monaldi Hospital Napoli

13Emeritus Medical Oncology FBF Hospital Milano

14Department of Oncology, Ospedale Umberto I Medical Oncology, ASP Siracusa, Italy

15Medical Oncology Casa di Cura Piacenza

*Corresponding Author: Sandro Barni, Emeritus Medical Oncology, ASST BG Ovest Treviglio Hospital Piazzale Ospedale 1 Treviglio (Bergamo). ORCID iD: https//ordid.org/0000-0002-7633-0378

Abstract

Background: Italian Ministerial Decree 77 has approved dehospitalization for chronic patients and has defined the territorial structures where a series of services will be provided and which will be managed by general practitioners (GP) and/or nursing staff.

Material and Methods: CIPOMO (Collegio Italiano Primari Oncologi Medici Ospedalieri) carried out a survey by sending a questionnaire to the heads of oncological departments of public hospitals (HODPH). The questionnaire included eleven questions concerning which activities are carried out, where can territorial oncological activities be carried out which ones and by whom. What are the possible obstacles, how the activity of the oncologists should be carried out.

Results: 124/165 anonymous questionnaires were received with a response rate of 75.6%. There are no territorial oncological assistance realities for 60% of the respondents. 25% think that some activities can be provided at home but most (75%) would prefer them in structures such as community hospitals or health homes. 80% of HODPH underline the serious shortage of healthcare personnel. The activities considered appropriate on the territory are the follow-up +/- oral and supportive therapies (84.8%). Follow-up can be done by the oncologist for 23.5% or together with a GP for 72.7%. The physical presence of an oncologist from the hospital staff is desired by 50.4% of respondents, 24.3% would prefer an oncologist dedicated to territory and 30% would prefer a virtual presence or on request.

Conclusions: The results show the interest of HODPH are actively participating in the dehospitalization of some oncological activities, but not only, for follow-up.

Keywords: Territorial oncology, Dehospitalization, Clinician's opinion, Ministerial decree, Survey

Introduction

According to recent AIOM data the number of new cancer cases in Italy is steadily increasing and the estimated new cancer diagnoses in 2023 are 395,000, 208,000 men and 187,000 women, compared with a steady reduction in the number of oncological deaths [1]. This reflects the important progress of Oncology in our country: cancer is increasingly becoming a curable disease and many patients can be called cured; in fact, there are about 1 million people in our country who have been cured of cancer. The 2020 data show that more than 3.6 million Italian citizens are living with a previous cancer diagnosis, that is, about 5.7 % of the Italian population, with an annual increase of 3% [2]. On December 7, 2023, the so-called "Forgetting Law" was finally passed, which allows patients who have been out of treatment for at least 10 years do not necessarily have to mention their oncological past [3]. In this demographic backdrop of increasing numbers of chronic patients, long-term and/or cured oncology patients, there is a decrease in the healthcare workforce. but an increasing of multimorbidity and medical complexity related to both new therapies and new toxicities grow. In addition, management complexities related to the economic sustainability of care are increasing with a progressive depletion of beds and care capacity of the public health system. The DM77, acknowledging the opportunity and socio-health need to develop territorial medicine or also called "proximity medicine," promotes dehospitalization for chronic patients and defines out-of-hospital health facilities for this purpose. It is not yet clear what activities will be able to be territorialized also in view of the fact that anticancer drugs available in oral formulation are gaining an increasingly important weight in the context of cancer therapies and cancer patients could be followed for a significant part of their treatment pathway on the territory with obvious positive effects in terms of quality of life and social, as well as human, costs. In addition, it is known that proximity of care favorably affects the time to diagnosis, appropriateness and compliance to treatment resulting in improved outcome and quality of life [4]. There are currently no documents or publications reporting what think about DM 77 the directors of public oncology hospital who will necessarily have to manage this transition to the territory. For this reason, CIPOMO decided to involve them with a nationwide survey.

Materials and Methods

A survey with a questionnaire consisting of 11 questions was sent to 165 hospital oncology directors in June 2022.

Table 1: The questionnaire submitted to hospital oncology chiefs.

|

Questions |

Possible Answers |

|

1- Are oncology care models active in your territory? |

- No - Yes in separate hospital presidia - Yes in community hospitals - Yes in health homes and/or community-home - Home |

|

2- If yes, they are active for: |

- Follow up - Oral and/or subcutaneous therapies - EV therapies |

|

3-In which territorial facilities do you think oncology care activities can be carried out? |

- In separate hospital presidia - In community hospitals - In health homes and/or community home - At home |

|

4-What could be the obstacles to the territorialization of oncology? |

- None - Shortage of staff to cover the territory - Clinical risk (for therapies). - Risk of inappropriateness for undertreatment - Risk of inappropriateness for overtreatment. - Inadequate information |

|

5- Do you think that in community facilities it is appropriate to do : |

- Follow up only. - Follow up, oral therapies, sc, im. - Follow up, oral and supportive therapies. - Subject to staff training and in a safe mode, including EV treatments |

|

6- Do you think follow up should be performed by: |

- GP - GP in close collaboration with the referring oncologist - The Oncologist |

|

7- If you believe that some oral treatments of low complexity can be safely followed at the territorial facility, who could do it? |

- GP in collaboration with the Oncologist - The Oncologist - Dedicated nurse in collaboration with the Oncologist - I do not believe that oral therapies can be performed outside the hospital |

|

8- The Oncologist present in territorial facilities must be: |

- An Oncologist dedicated only to the territory - An Oncologist from the hospital who in turn is physically present on the territory - An Oncologist from the hospital who in turn is connected via web with the territory - An Oncologist from the hospital who can be contacted on demand - I do not consider the presence of an oncologist on the territory to be functional |

|

9- If the level of care and organization is adequate do you believe that clinical trials can be carried out in peripheral facilities ? |

- Yes/no |

|

10- Do you believe that selected patients who are physically and/or socially frail can safely undergo active therapies at their homes? |

- Yes/no |

|

11- Do you think "Early Palliative Care" is necessary and should be implemented: |

- Mainly at the hospital level - Mainly at the territorial level (GPs,Local Palliative Care Network. - In a network relationship between hospital territory and intermediate facilities (including hospice) - I consider it not feasible |

Table 1shows the 11 questions regarding the current presence of oncology care models in the territory, what activities are carried out there, where the territorial oncology activities can be carried out, which ones and by whom, what are the possible obstacles, how the oncology specialist's activities should be carried out, and whether they think it is possible to carry out clinical trials in the territory.

Results

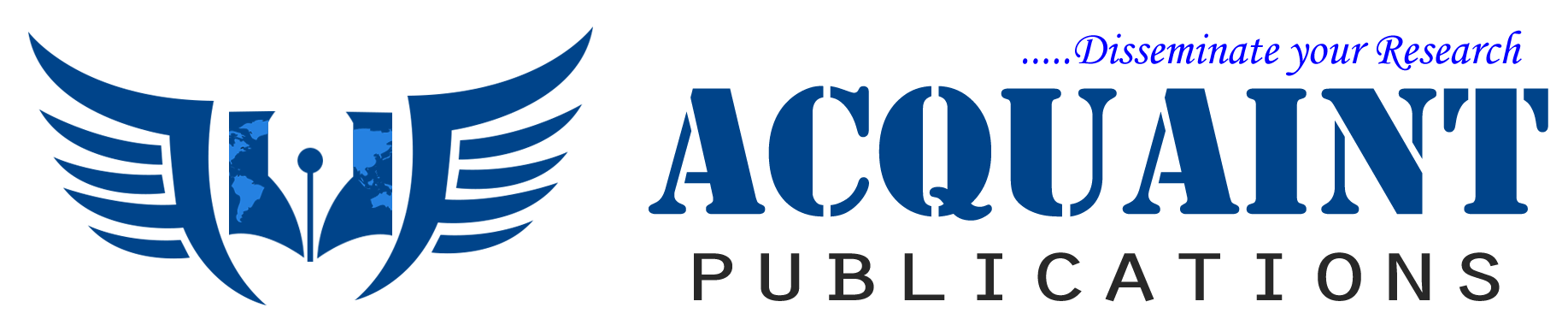

Responses to the CIPOMO Survey questionnaire were obtained from 124 directors anonymously and then analyzed. The analysis shows that there are currently no territorial oncology care settings for 60% of the respondents and when they do exist, they mainly provide follow-up services (40%). To date only 25% of oral and/or subcutaneous therapies and 33% of intravenous therapies are done in the territory. If we now turn to the opinions expressed by primary oncologists to the question "in which territorial facilities they believed oncology care could be carried out" there is a wide disparity of opinion, but only 25% believe that some activities can be delivered at home while most (75%) would prefer them in facilities such as community hospitals or health homes.

Figure No.1: Where oncologist think oncology care can be carried out

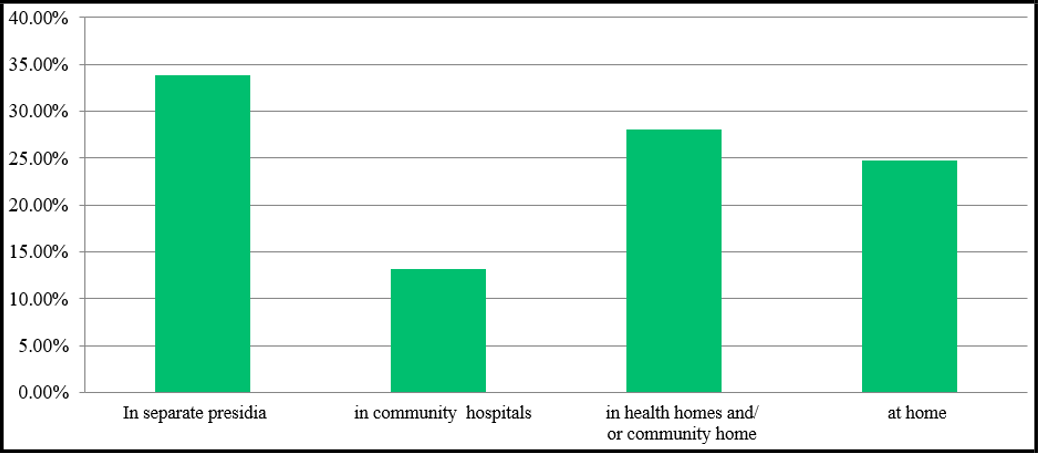

To the question "What could be the obstacles to territorialization of oncology" 80% answered:lack of staff to cover the territory as well.

This to stress what are the comments of many italian citizens to DM 77 which provides funds for facilities and few for staff. (Figure 2)

Figure No.2: What could be the obstacles to the territorialization of oncology

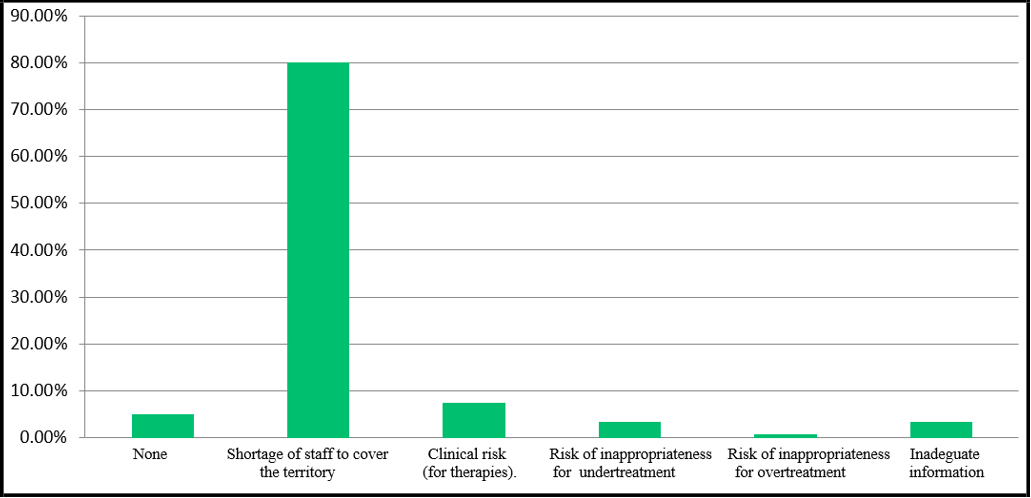

Is also important to understand what activities oncologists would consider appropriate in the area. Follow-up +/- oral and supportive therapies are those considered appropriate by 84.8% of respondents, and only 15.1% believe that chemotherapy or IV immunotherapy can be done, but only with adequate staff training.

Figure No.3: What services could be performed in the territory

Follow-up is certainly considered by the majority to be absolutely feasible in out-of-hospital facilities, and when asked by whom it should be done, the answer is by the oncologist only for 23.5 % or together with the family doctor for 72.7 %.

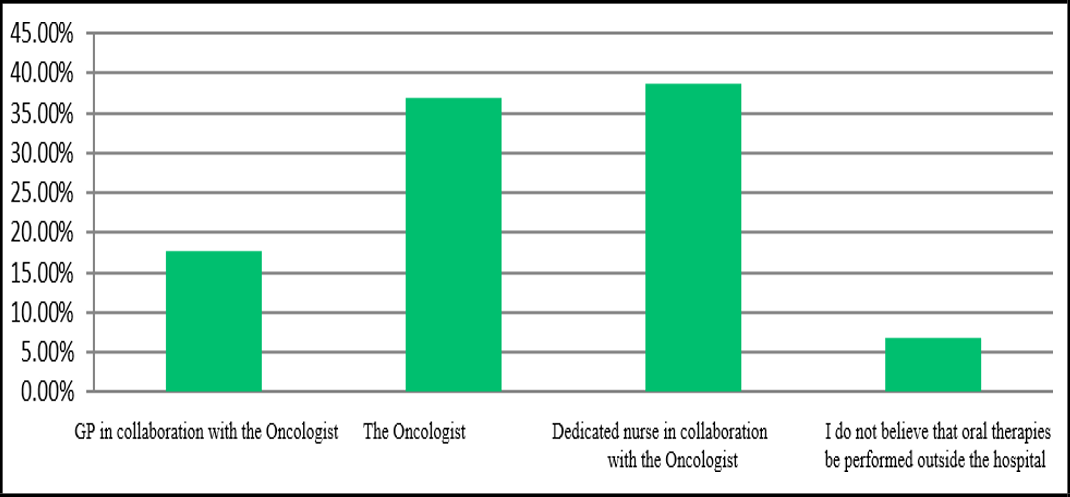

The feasibility of oncology therapies is basically related to the issue of patient safety. This issue arises especially for oral therapies, which are steadily increasing today. Those with low complexity are considered feasible outside hospital by 93.2%, but only if managed by the oncology specialist also in collaboration with the family physician and/or nurse.

Figure No.4: Who could do low-complexity oral treatments safely in the territorial facility.

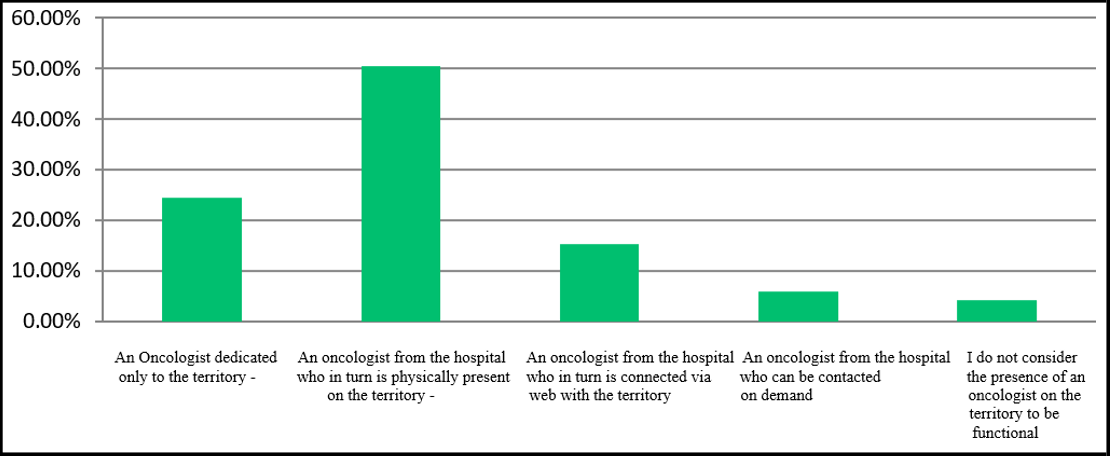

Related to the shortage of health care staff is the question of what the oncologist working in the territory should look like. The physical presence of a hospital staff oncologist is desired by 50.4% of respondents, 24.3% would prefer an oncologist dedicated only to the territory, and 30% a virtual or on-demand presence.

Figure No.5: What figure of Oncologist in the territory.

Traditionally, medical oncology cannot do without clinical research especially when there is a major reevaluation of real life data. When asked whether they consider clinical trials in peripheral network hospitals feasible, provided the level of care and organization is adequate, 62.1% said yes.

Almost similar result that of the percentage (59.2%) of those who believe that selected patients who are physically and/or socially frail can safely undergo active therapies at their homes.

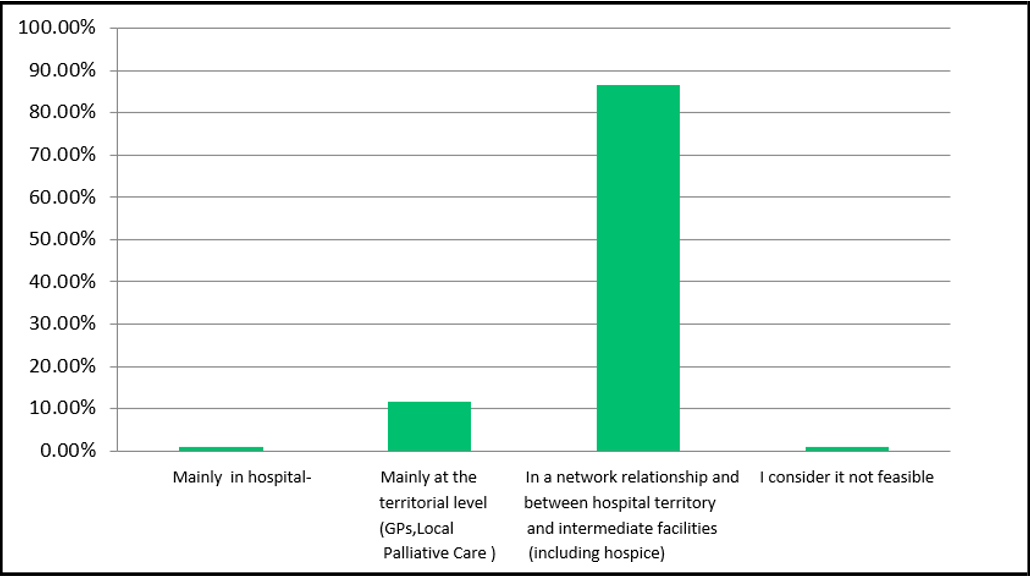

Lastly, oncologists consider necessary to implement "Early Palliative Care" in the proportion of 98% of which 86.5% in a networked relationship between hospital,territory and intermediate facilities including hospices.

Figure No.6: Need for implementation of "Early Palliative Care" .

Discussion

DM77 has been a stimulus for CIPOMO to seek solutions on how to manage the inevitable shift from hospital-centric medicine to proximity-centric medicine, that is, closer to the patient and to where he or she lives. It is not yet clear what oncology activities will be able to be done in the local area with the same safety as in the hospital, and this will depend on local possibilities and on the preparation of the practitioners involved who are clamoring for this upgrade. This shift is now necessary in view of the ever-increasing number of patients who are cured or chronically treated because of the results achieved through biomolecular and pharmacological innovations. So many patients are cured permanently that we can finally arrive at a law of oblivion [3].

Now immunotherapy makes it possible to achieve survivals of years even for patients with metastatic disease who previously had a prognosis of only few months, such as melanoma [4,5], lung cancer [6-8], some urologic cancers [9] and many others in which trials are yielding unexpected results.

There is a growing debate on financial difficulties [10,11] and it becomes important to note how adequate territorial facilities can ensure, while keeping safety intact, that the patient can greatly reduce the "burden" of travel [12] with associated loss of time, economic expenses and loss of work days of caregivers [13,14].

Another element in favor of dehospitalization should be taken into account: oncology drugs tend to be administered more easily, by mouth or subcutaneously, making access to the hospital less essential, although the safety and appropriateness of treatments should never be underestimated. For another, it has long been known that patients are extremely supportive of these treatments as long as they are aware of their safety [15-20]. It remains, once again fundamental, that the patient has to be convinced that his or her treatment is no less effective and safe than it could be if done in the hospital, as, is referred to in the Patients' Bill of Rights [21]. Italian studies have been published that highlight how a proximity oncology is possible in our country, bringing oncology care, and not only oral care, close to the patient's home with considerable savings in time and miles, also avoiding the need to be accompanied by caregivers [22-25]. Such care can be provided in community hospitals or even in specially equipped facilities (Community Homes, Health Homes) in rural areas where hospitals are lacking [23].

This model sees professionals rotating from the main referral hospital to outlying sites to care for oncology patients.

CIPOMO's survey made it possible to capture and make available to the legislators the thoughts of the heads of the oncological department who will have to manage this important transition to territorial medicine. The message is the willingness to grapple with this not easy task that will require from everyone an important change of mentality, combined still with doubts about the methodologies to be used and operational strategies that will necessarily have to confront with the various local realities. The essential concept remains that territorial cancer care must be an integral part of the oncology network and of the comprehesive cancer center network "spread out to the territory [24,26].

The role of the GP also in this transitional phase is extremely important, and for this reason. Last year CIPOMO organized a meeting with GP representatives from all Italian regions who were highly supportive of dehospitalization, subject to a period of educational training that is currently being prepared with the Italian Medical Association. In fact, community homes/ community hospitals would be managed both administratively and clinically by GPs and nurses.

Conclusion

Ministerial Decree 77, with PNRR funds, approved dehospitalization for the chronically ill and defined the territorial facilities where a range of services will be provided and that will be managed by general practitioners and/or nursing staff. As for oncology, the types of services and how the oncologist will be involved have not yet been determined.

The thoughts of 124 CIPOMO oncology directors, expressed through their responses to the questionnaire point out some important aspects that deserve much attention from those who will have to manage this transition and this socio-health but also cultural change.

The results show:

- the interest of hospital oncology directors in dehospitalization of some oncology activities, especially, but not only, for follow-up, and the interest in clinical research "spread" across the territory.

- the desire to collaborate with the GP and nursing staff, who need and demand adequate educational support to ensure the oncology patient the same quality of care, safety, and appropriateness close to home, resulting in a better quality of life, obvious time savings, and also cost reductions.

- emphasize some aspects still lacking and more so the shortage of staff.

- auspy the realization of a nationwide oncology network in which the transition of medicine to the territory can take place without differences in care and outcome for patients and that the territory is a "node" of the oncology network.

Finally, oncologists hope that in the future, when faced with major health care decisions, the experience of those who deal with the real problems of patients every day will be taken into consideration in advance.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Cristina Giua (CIPOMO secretary) for her coordination of work.

Declaration of conflicting interests: no conflict of interest to declare

Author contributions

SB, CA, LB, MG, CO, GP, FA, LF, BD, GA, RRS, VM, AS, PT, acquired, analyzed or interpreted data; critically reviewed anddrafted the manuscript; provided final approval, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- AIOM (2023) I numeri del cancro in Italia 2023. Brescia:Intermedia Editore 2023.

- Guzzinati S, Virdone S, De Angelis R, Panato C, Buzzoni C, et al. (2018) Characteristics of people living in Italy after a cancer diagnosis in 2010 and proiections to 2020. BMC Cancer. 18: 169.

- Legge 7 dicembre 2023, n. 193: Disposizioni per la prevenzione delle discriminazioni e la tutela dei diritti delle persone che sono state affette da malattie oncologiche. G.U. n. 294 del 18 dicembre 2023

- Dummer R, Flaherty KT, Robert C, Arance A, de Groot JWB, et al. (2022) COLUMBUS 5-Year Update: A Randomized, Open- Label, Phase III Trial of Encorafenib Plus Binimetinib Versus Vemurafenib or Encorafenib in Patients With BRAF V600– Mutant Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 40(36): 4178-4188.

- Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Carlino MS, Mitchell TC, et al. (2021) Long-term outcomes in patients with advanced melanoma who had initial stable disease with pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-001 and KEYNOTE-006. European Journal of Cancer. 157: 391-402.

- Brahmer JR, Lee JS, Ciuleanu TE, Bernabe Caro R, Nishio M, et al. (2023) Five-Year Survival Outcomes With Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab Versus Chemotherapy as First-Line Treatment for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in CheckMate 227. J Clin Oncol. 41(6): 1200-1212.

- Novello S, Kowalski DM, Luft A, Gümüş M, Vicente D, et al. (2023) Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Squamous Non- Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Update of the Phase III KEYNOTE-407 Study. J Clin Oncol. 41(11): 1999-2006.

- Garassino MC, Gadgeel S, Speranza G, Felip E, Esteban E, et al. (2023) Pembrolizumab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum in Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes From the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 Study. J Clin Oncol. 41(11): 1992-1998.

- Powles T, Park SH, Caserta C, Valderrama BP, Gurney H, et al. (2023) Avelumab First-Line Maintenance for Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma: Results From the Javelin Bladder 100 Trial After ‡2 Years of Follow-Up. J Clin Oncol. 41(19): 3486-3492.

- Lentz R, Benson AIB, Sheetal Kircher S (2019) Financial toxicity in cancer care: Prevalence, causes, consequences, and reduction strategies. J Surg Oncol. 20(1): 85-92.

- Perrone F, Jommi C, Di Maio M, Gimigliano A, Gridelli C, et al. (2016) The association of financial difficulties with clinical outcomes in cancer patients: secondary analysis of 16 academic prospective clinical trials conducted in Italy. Annals of Oncology. 27(12): 2224–2229.

- Ambroggi M, Biasini C, Del Giovane C, Fornari F, Cavanna L (20215) Distance as a Barrier to Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment: Review of the Literature. The Oncologist. 20(12): 1378–1385.

- Uehara Y, Koyama T, Katsuya Y, Sato J, Sudo K, et al. (2023) Travel Time and Distance and Participation in Precision Oncology Trials at the National Cancer Center Hospital. JAMA Network Open. 6(9): e2333188.

- Gupta A, Eisenhauer EA, Booth CM (2022) The Time Toxicity of Cancer Treatment. J Clin Oncol. 40(15): 1611-1615.

- Twelves C, Gollins S, Grieve R, Samuel L (2006) A randomized crossover trial comparing patient preference for oral capecitabine and 5-fluorouracile/leucovorin regimens in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Annals of Oncology. 17(2): 239-245.

- Liu G, Fransen E, Fitch M, Warner E (1997) Patient preferences for oral versus intravenous palliative chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 15(1): 110-115.

- Catania C, Didier F, Leon M (2005) Perception that oral anticancer treatments are less efficacius: developement of a questionnaire to asses the possible prejudices of patients with cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 92(3): 265-272.

- Ciruelos EM, Díaz MN, Isla MD, López R, Bernabé R, et al. (2019) Patient preference for oral chemotherapy in the treatment of metastatic breast and lung cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 28(6): e13164.

- Havrilesky LJ, Scott AL, Davidson BA, Secord AA, Yang JC, et al. (2021) The preferences of women with ovarian cancer for oral versus intravenous recurrence regimens. Gynecol Oncol. 162(2): 440-446.

- Barni S, Aschele C, Blasi L, Giordano M, Ortega C, et al. (2024) What patients with cancer think about the dehospitalization. A survey of CIPOMO. Recenti Prog Med. 115(5): 232-237.

- Active Citizenship Network. Carta europea dei diritti del malato. 2002

- Cavanna L, Citterio C, Di Nunzio C, Zaffignani E, Cremona G, et al. (2021) Territorial-based management of patients with cancer on active treatment following the Piacenza (north Italy) Model. Results of 4 consecutive years. Recenti Prog Med. 112(12): 785- 791.

- Mordenti P, Proietto M, Citterio C, Vecchia S, Cavanna L (2018) La cura oncologica nel territorio. Esperienza nella Casa della Salute: risultati preliminari nella provincia di Piacenza. Recenti Progres Med. 109(6): 337-341.

- Cavanna L, Citterio C, Mordenti P, Proietto M, Bosi C, et al. (2023) Cancer Treatment Closer to the Patient Reduces Travel Burden, Time Toxicity, and Improves Patient Satisfaction, Results of 546 Consecutive Patients in a Northern Italian District. Medicina (Kaunas). 59(12): 2121.

- Fattore G, Bobini M, Meda F, Pongiglione B, Baldino L, et al. (2024) Reducing the burden of travel and environmental impact through decentralization of cancer care. Health Serv Manage Res. 2: 9514848241229564.

- Barni S, Blasi L, Bosi C, et al. (2023) Il ruolo del territorio in una nuova organizzazione dell’oncologia. Firenze, Koncept 27 ottobre.