Kusay Abdulhameid Almusa*

Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiology, Al Kuwait Hospital, Dubai, Emirates Health Service (EHS) UAE

*Corresponding Author: Kusay Abdulhameid Almusa, Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiology, Al Kuwait Hospital, Dubai, Emirates Health Service (EHS) UAE

Abstract

Pulmonary Tuberculosis (PTB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is a potentially serious infectious disease that mainly affects the lungs, and it is a leading cause of infectious disease morbidity and mortality worldwide and resistance to commonly used anti tuberculous drugs is increasing [1]. PTB may also disseminate (miliary TB) or affect almost any other organ (extra pulmonary TB): pleural cavity, pericardium, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract and peritoneum, genitourinary tract, skin, bones and central nervous system [2].

Most commonly, PTB is transmitted via aerosol droplets from infectious patient. The global incidence of TB peaked around 2003 and appears to be declining slowly [1]. However, PTB disease cases have been climbed since 2020 and increased 5% in 2022 but did not return to pre- pandemic levels [3]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2021, 10.6 million individuals became ill with PTB and 1.6 million died, and globally in 2022, more than 410,000 people developed rifampin-resistant or multidrug-resistant (MDR) PTB [4].

Keywords: pneumonitis, first and second line anti tuberculous medications

Introduction

After Inhalation of Aerosolized Droplets Containing Tuberculosis By A Susceptible, Previously Uninfected Individual Leads To Deposition In The Lungs, With One of The Following Possible Outcomes [5]:

1. Immediate clearance of the organism before an adaptive response develops.

2. TB infection (previously termed latent TB) refers to containment of viable organisms via host immunity with evidence of specific cell-mediated immunologic response to M tuberculosis (e.g. positive Interferon- Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) in the absence of signs or symptoms of illness.

3. Reactivation disease (or post primary TB are often used interchangeably) to describe occurrence of TB after a period of clinical latency.

Individuals infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) may develop symptoms like: cough, hemoptysis, fever, weight loss, night sweats and chest pain (it can also result from tuberculous acute pericarditis) [6].

The diagnosis of PTB should be suspected in patients with relevant clinical manifestations, is definitively established by isolation of M. tuberculosis from a bodily secretion or fluid (e.g. culture of sputum, Broncho-alveolar lavage, or pleural fluid) or tissue (e.g. pleural biopsy or lung biopsy).

The detection of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) on microscopic examination of stained sputum smears is the most rapid and inexpensive TB diagnostic tool. Absence of a positive smear result does not exclude active TB infection; AFB culture is the most specific test for TB and it benefit for culture-based drug susceptibility testing [7].

Other Diagnostic Testing May Warrant Consideration, Including The Following:

1. Nucleic acid amplification tests

2. Specific enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot).

3. Blood culture

4. HIV serology in all patients with TB, as individuals infected with HIV are at increased risk for TB.

Screening of PTM by interferon-gamma release assays (IGRA) and Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) is reserved for: higher risk people of being exposed to TB germs or higher risk of developing TB disease like HIV and cancer patient. However, TST and IGRAs are used to diagnose LTBI and should not be used to exclude the possibility of active tuberculosis [ 8, 9].

Patients meeting clinical criteria should undergo chest radiography. However, no radiological features are themselves diagnostic and often active PTB cannot be distinguished from inactive disease based on radiography alone. The Common findings suggesting PTB are: unilateral or bilateral focal infiltration of the upper lobe or the lower lobe(s), cavitation may be present, and inflammation with tissue destruction may result in fibrosis, traction and/or enlargement of hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes [7]. Chest computed tomography (CT) is more sensitive than plain chest radiography for identifying early or subtle parenchymal and nodal processes. It may be reserved for circumstances in which more precise definition of features observed in a chest radiograph is required or where an alternative diagnosis is suspected [7].

A 6-month treatment regimen composed of four first-line TB medicines including intensive phase of two months with 4 drugs:

1. Isoniazid, Rifampin, Pyrazinamide, and Ethambutol, followed by the continuation phase of at least four months with 2 drugs of Isoniazid and Rifampin (known as 2HRZE/4HR), it recommended for treatment of drug- susceptible TB [10].

2. This regimen is well known and has been widely adopted worldwide for decades; while using it, approximately 85% of patients will have a successful treatment outcome with unique considerations for the 4-month PTB treatment regimen: of isoniazid, rifapentine, moxifloxacin and pyrazinamide (2HPMZ/2HPM) [10].

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB, defined as M. Tuberculosis with resistance to at least Isoniazid and Rifampin and possibly additional anti-tuberculous agents) with inconsistent findings on the association between HIV infection and MDR-TB were present in many studies. Treatment of MDR- PTB can be difficult and may necessitate use of second-line drugs and/or surgical resection and the most important predictors of drug-resistant TB are [11, 12]:

1. 1-A previous episode of TB treatment.

2. Persistent or progressive clinical and/or radiographic findings while on first-line TB therapy.

3. Residence in or travel to a region with high prevalence of drug- resistant TB.

4. Exposure to an individual with known or suspected infectious drug- resistant TB.

For treatment of MDR /rifampicin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB), the WHO recommends 6-month Bedaquiline, Pretomanid, Linezolid, and moxifloxacin (BPaLM) rather than 9- month or longer regimens [13]. While treatment of extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB: tuberculosis that resistance to isoniazid, rifampin, a fluoroquinolone and either bedaquiline or linezolid) is typically longer and often associated with a higher likelihood of toxicity and regimens should be chosen in consultation with an individual who has expertise with treatment of MDR- TB, and in collaboration with a public health TB treatment program that can provide the infrastructure for safe completion of treatment [14].

Pulmonary complications of TB include hemoptysis, pneumothorax, bronchiectasis, extensive pulmonary destruction, fistula, tracheobronchial stenosis, malignancy, and chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. These complications occur more commonly in the setting of reactivation disease [15]

Case Report

Clinical Case Summary Patient: 20-year-old male

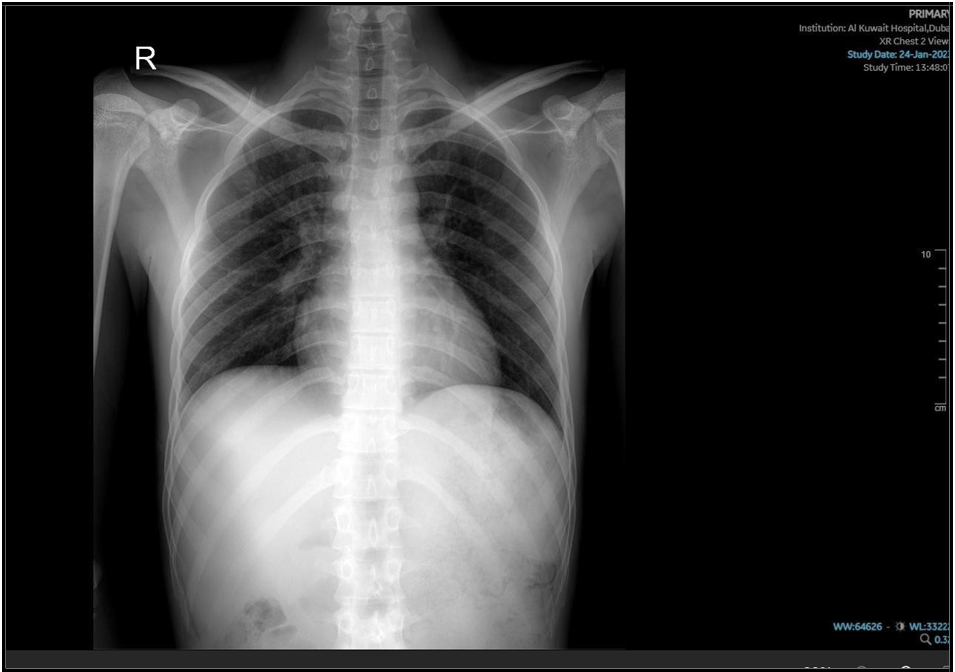

Presenting Issue: Detected active pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) on routine chest X-ray during a resident visa application.

Contact History: Positive TB contact – grandmother diagnosed with TB 6 months prior.

Symptoms: Mild productive cough for 2 weeks, with minimal expectoration

|

Test |

Result |

|

Vitals |

Stable |

|

Chest X-ray |

Suggestive of active pulmonary TB |

|

PCR for MTB |

Positive |

|

ESR |

27mm/hr (mild elevation) |

|

CRP |

22 mg/L (mild elevation) |

|

Sputum Smear/Culture |

Awaiting results |

|

HIV test |

Negative |

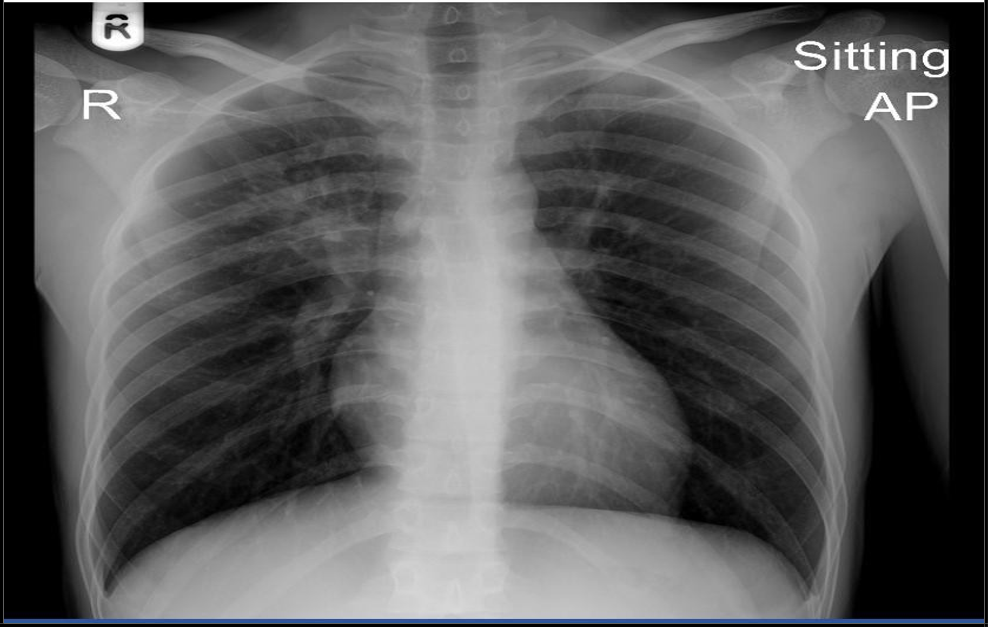

(“18 Nov 2024”) Inhomogeneous opacity with a cavity formation is seen in right mid zone in para hilar region.

He started with the intensive phase of 4 medications for the 6 months anti tuberculous regime; his cough had improved, as well as follow- up lab test of CBC, electrolytes-renal functions and LFT were all normal, while CRP dropped to 8.7 and ESR to 10. The repeated chest x-ray, performed 2 weeks after initiating therapy, demonstrated mild improvement of the initial findings. The Mycobacterial culture confirmed sensitivity to both Rifampicin and Isoniazid, which supports the continued use of the standard first-line anti-TB regimen.

(“05 Dec. 2024”) Slight improvement of the opacity is seen

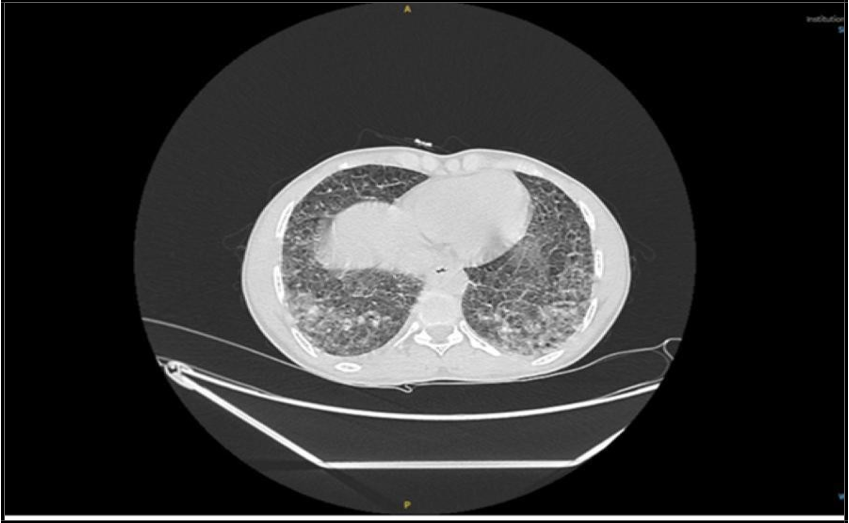

After three weeks on the four-drug anti- tuberculous regimen, the patient deteriorated, initially presenting with a mild, itchy maculopapular rash, followed by the onset of nausea and pyrexia. He was treated symptomatically, and pyrazinamide was discontinued as it was suspected to be the cause of the rash. Although his initial symptoms began to improve following the discontinuation of pyrazinamide, within a few days the patient deteriorated further— developing shortness of breath, elevated inflammatory markers (CRP increased to 87 mg/L, Procalcitonin to 0.6 ng/mL), and a one-fold elevation in transaminase liver enzymes. A requested sputum culture failed to identify any superadded bacterial or fungal pathogens. High- resolution CT chest done and showed a progressive course.

(“29 Dec. 2024”) CT showed Focal patchy consolidative opacity noted in right upper lobe with multiple poorly defined linear and reticulo- nodular opacities in bilateral lower lobes.

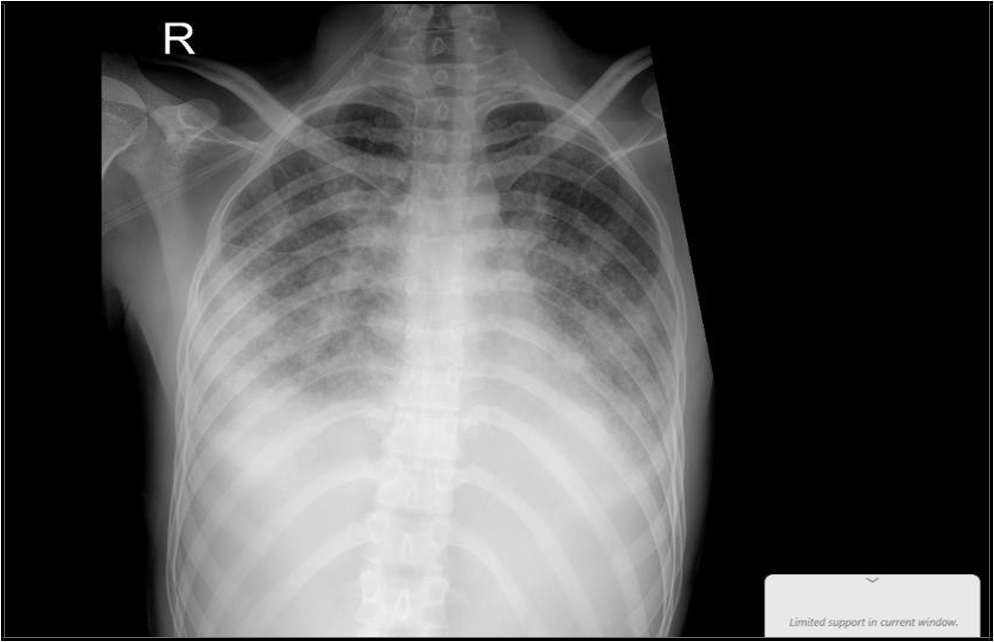

Due to the progression of symptoms— including worsening shortness of breath, a drop in SpO₂, and a generalized skin rash— the patient was transferred to the ICU and initiated on oxygen support. A repeat chest X-ray revealed features consistent with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). This was accompanied by a progressive rise in inflammatory markers (CRP increased to 154 mg/L, procalcitonin to 15 ng/mL), and a five-fold elevation in liver transaminase levels. Viral screening tests for Measles, Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Rubella were requested and all returned negative. The Electrocardiogram (ECG) was unremarkable, and echocardiography revealed normal wall motion and thickness, with a preserved ejection fraction of 55%. However, Pro-BNP was markedly elevated at 3000 pg/mL. Following evaluation by the infectious disease consultant, first-line anti- tuberculous medications were discontinued, and second-line anti-TB therapy was initiated along with a course of corticosteroids.

(“03 Jan. 2025”), Progressive patchy alveolar infiltrate, moderate Rt side effusion.

He kept on—based on the availability of second-line agents—with Imipenem-cilastatin, levofloxacin, linezolid, and prednisolone, along with the continuation of ethambutol and ongoing oxygen support. After a few days, his condition stabilized, and he was gradually weaned off oxygen support before being transferred back to the medical ward. His inflammatory markers showed progressive improvement, and liver enzyme levels returned to normal.

(“16 Jan 2025”) Significant changes noted, with improvement of patchy alveolar infiltrate, still hazy left CP angle.

He was discharged from the medical ward three weeks later after three consecutive negative acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smears. He was advised to continue his medications as an outpatient and to follow up at the preventive medicine clinic. At the subsequent clinic visit, his condition was stable, and a repeat chest X-ray showed radiological improvement. His current treatment regimen was continued.

(“29 Jan 2025”) Improvement of the previous disease

Discussion

The Differential Diagnoses for This Case Included:

1. Extensive pulmonary destruction (Rarely, untreated or Inadequately treated TB can cause progressive, extensive destruction of areas of one or both lungs) [15].

2. Hospital-acquired pneumonia (This was considered unlikely, as both cultures and viral screening were negative).

3. Tuberculosis -immune reconstitution Inflammatory syndrome which is an excessive immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis that may occur in either HIV-infected or uninfected patients, during or after completion of anti-TB therapy [16].

4. Paradoxical reaction to anti TB drugs medications.

5. Tuberculous relapse (is a possibility; however, less likely given the good initial response to therapy.

This patient was minimally symptomatic and was diagnosed incidentally. He initially demonstrated a good clinical and radiological response; however, his condition later deteriorated, beginning with the development of a skin rash, followed by a flare- up of the disease, as evidenced by clinical deterioration and by findings on chest X-ray / CT scan. After being shifted to the ICU, he was started on a short course of steroids, while rifampicin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide were discontinued. He was initiated on second-line anti-TB medications, following which he showed good response and clinical improvement.

Pulmonary Toxicity Secondary To Drugs May Be Due To A Variety Of Mechanisms, Such As The Following:

1. Immune system–mediated injury.

2. Oxidant injury.

3. Pulmonary vascular damage.

4. Deposition of phospholipids within cells

5. Central nervous system (CNS)depression.

6. Direct toxic effect [17].

The Most Likelihood Offending Drug(S) Are:

Rifampicin: the most likely offending drug as it may associated with hypersensitivity reactions and can cause both pulmonary toxicity and pulmonary infiltrates [18].

Isoniazid (INH): less commonly than rifampicin, INH-induced pneumonitis is a rarely observed complication, and drug-induced lupus erythematosus is another rare, adverse event that might lead to pulmonary vasculitis [19].

Ethambutol: rare reports of hypersensitivity pneumonitis [20], as the main side effects are eye damage, Changed color vision and skin rash [21]. This medication was not discontinued in this patient; therefore, it was unlikely to be the cause of the clinical deterioration.

Pyrazinamide: least likely, as the main side effects: hepatic toxicity, gout, stomach upset and skin rash [21].

Conclusion

Based on the clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings, rifampicin was considered the most probable cause of the deterioration, likely mediated by hypersensitivity and immune-mediated lung injury.

To determine whether anti-tuberculosis drug–induced pneumonitis is the most probable diagnosis, several clinical factors must be considered, including the onset of symptoms, medication history, timing of clinical deterioration, and the subsequent response to second-line anti-tuberculosis therapy

References

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2020.

- Torok ME, Moran ED, Cooke FJ (2017) Oxford Handbook of infectious diseases and microbiology, second edition.

- CDC (2023) Preliminary TB data released by CDC ahead of World TB Day. NCHHSTP Newsroom.

- Bagcchi S (2023) WHO’s Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. Lancet Microbe. 4(1): e20.

- Pozniak A (2024) Pulmonary tuberculosis: clinical manifestations and complications. UTD.

- Sahra S (2024) Department of Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases, Oklaho ma University of Health Sciences Center. Medscape

- Bernardo J (2024) Diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in adults. UpToDate.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2024) H5 Bird Flu: Current Situation. Avian Influenza (Bird Flu).

- De Lima Corvino DF, Shrestha S, Hollingshead CM, Kosmin AR (2023) Tuberculosis Screening, National Institute of Health.

- WHO (2022) WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment - drug- susceptible tuberculosis treatment.

- Barry PM, Cattamanchi A, Chen L, Chitnis AS, Daley CL et al. (2016) Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: A Survival Guide for Clinicians, Third Edition. Curry International Tuberculosis Center.

- WHO (2015) Global tuberculosis report.

- WHO (2023) WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment - drug- resistant tuberculosis treatment.

- WHO (2022) Rapid communication: Key changes to the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis.

- Pozniak A (2025) Pulmonary tuberculosis disease in adults: Clinical manifestations and complications. UpToDate.

- Infectious Diseases Unit (2016) Infectious Diseases Unit, “G.B. Rossi” University Hospital, Verona, Italy B Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Nazarbayev University, Astana, Kazakhstan Sandro Vento, published in National Library of Medicine.

- By Klaus-Dieter Lessnau (2025) Medscape eMedicine.

- Drew RH (2025) Rifamycins (rifampin, rifabutin, rifapentine). UpToDate.

- Martin TCS, Hill LA, Michael ET, Balcombe SM (2020) International Journal of infectious disease. Elsevier. 100: 470-472.

- Takami A, Nakao S, Asakura H, Yamazaki H, Mizuhashi K et al. (1997) Pneumonitis and eosinophilia induced by ethambutol. The journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 100(5): 712-713.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2025) Adverse Events During TB Treatment. Tuberculosis (TB).