Bupe Khalison Mwandali*

University of Cincinnati, College of Nursing, 227 Procter Hall, 3100 Vine Street, Cincinnati Ohio 45221-0038, 513-302-2936.

*Corresponding Author: Bupe Khalison Mwandali, University of Cincinnati, College of Nursing, 227 Procter Hall, 3100 Vine Street, Cincinnati Ohio 45221-0038, 513-302-2936.

Abstract

Purpose: To determine how perceived gender inequality in women between 18 to 25 years affects their psychological well-being.

Methods: An integrative review design was conducted, guided by Whittemore and Kanfl's (2005) five steps. Published peer-review articles were searched from CINAHL, PubMed, Google Scholar, and other sources. Four papers were included in the review, organized and summarized in the table. The documents' quality was evaluated using Johns Hopkins, and all pieces were at level III (B).

Results: Higher prevalence of gender inequality was perceived among Black women more than White women from different settings, with a higher percentage in service provision (91.3 %). All articles showed direct connections between psychological effects and gendered racism. One study reported that 73 % of participants suffered from stress. Approximately all participants used disengagement as a coping mechanism, which in turn increased the psychological effects due to poor social support.

Conclusions: The magnitude of gender inequality was higher among African American women with poor coping and support systems, which increased the psychological distress among participants. The government and stakeholders should develop strategies that focus on integrating social systems and policies to support the reduction of gendered racism. The intersectionality framework was highly suggested in research and practice.

Keywords: Gendered inequality, women aged 18-25 years, emerging adults, African American Women, psychological well-being.

Introduction

Gender Inequality and Psychological Well-being

Emerging adulthood is an interim moment between adolescence and adulthood, from age 18 through age 25 and above [1]. This is a critical period for emerging adults to explore meaningful lives and discover their identities through education, love, and work [1]. Improved psychological well-being is associated will fewer depressive symptoms and raises self-esteem [2]. Therefore, it is essential to develop social-cognitive maturity with a broader understanding of themselves and others than in adolescence [1]. Despite a rising sense of well-being for many emerging adults, some experience more critical psychological-related health problems than depression [1].

Female emerging adults are more likely to experience psychological health problems associated with oppression due to multiple identities (such as gender, race, and class) interacting to increase discrimination and barriers to access opportunities [3]. Gender inequality creates unequal treatment between men and women in accessing and controlling resources and assets due to biological, physical, psychological, or cultural norms that exist within society [4].

Intersectionality is how certain aspects of a person (e.g., race, gender, class, and others) are multifaceted and connected, increasing privilege or oppression in accessing material and non-material things [3]. The Oxford Dictionary defines intersectionality as "The interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage" [5]. Mental distress is associated with the inability to perform well academically, a higher level of depression, anxiety, and substance abuse [6]. Joint strategies are required to address discrimination while encouraging a healthy and conducive environment for better functioning of psychological well-being [3,7]. This integrative review aimed to assess how gender inequality in women between the ages of 18 and 25 affects their sense of psychological well-being globally.

Methods

Problem Identifications

Emerging adulthood is a period to be handled with great care and support as individuals explore their identities [1]. Gender inequality is a global problem that deprives participants of rights [3]. Globally, less effort is reported to reduce gender inequality [3]. Literature shows that emerging female adults are predisposed to gender inequality due to societal perceptions placed on them. The male gender is highly privileged in societal rights and opportunities, which creates discrimination against the female gender [4].

Inequality experienced by female emerging adults subjects them to psychological distress and makes them unable to attain their future goals [3]. Information obtained from this review will help to generate new knowledge about the topic of interest by getting insightful information from the literature review, methodology, and conceptual framework. This study is essential in identifying the existing literature review on the perceived gender inequality in female emerging adults and how it affects their psychological well-being. Furthermore, the findings will lead to further qualitative exploratory studies being conducted globally.

Strategies Used for Searching and the Inclusion Criteria

The integrative review was conducted to identify the current research evidence to answer the stated purpose of the study. The author searched and was guided by Whittemore and Kanfl's (2005) five steps for the integrative review process (problem identification, literature, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation). Information was searched from online databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Google Scholar, and other sources). Gendered inequality, women aged 18-25 years, emerging adults, African American Women, psychological well-being. The inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed journals, papers published between 2007 to 2022, written in English, and using human subjects. The rationale for including papers published within 16 years; studies have yet to be conducted on this topic. Inclusion criteria were terms used in the keywords plus all study designs, human subjects, dissertations, and social discrimination.

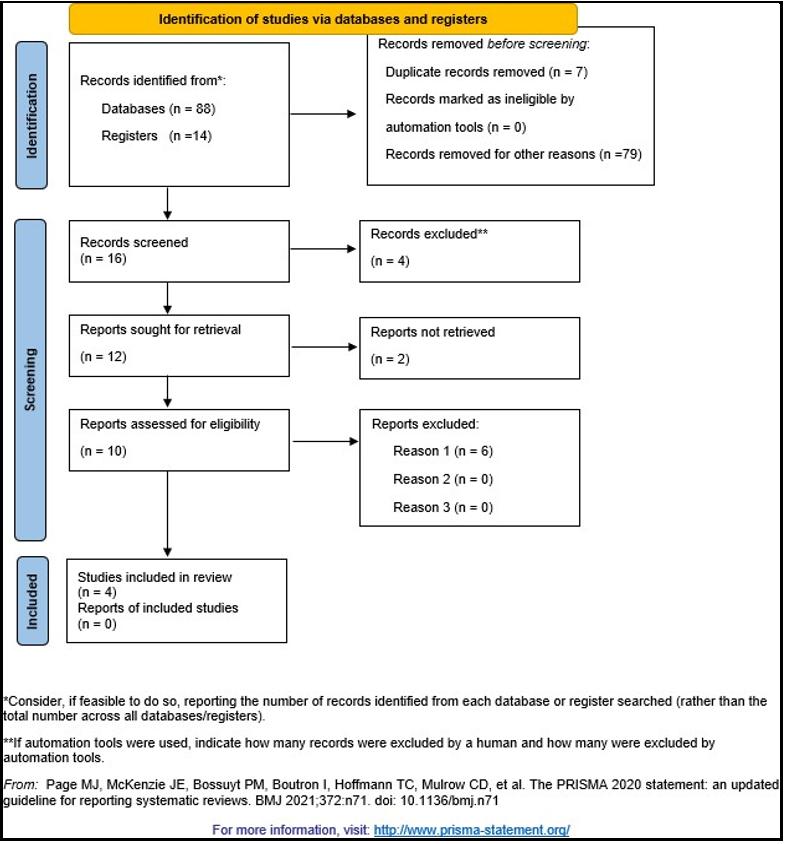

102 papers were identified: 88 from databases (38 from Google Scholar, 26 from PubMed, 24 from CINAHL), and 14 from registers. Eighty-six records were removed before screening; 7 were due to duplications, and 79 were published more than 15 years ago. From initial screening, 4 out of 16 were removed by reviewing the title and abstract alone; the removed papers did not fit the research questions. Two records were removed due to the unavailability of the full text. Finally, the researcher conducted a full-text review of 10 articles; 6 papers were omitted because they needed to answer the research question. Four (4) studies remained after the screening process was complete. Refer to PRISMA Figure 1.

Figure 1: Prisma Diagram of an Integrative Review on How Perceived Gender Inequality in Women Between 18 to 25 years Affects Their Sense of Psychological Well-being.

Design and Samples

The design was an integrative review.

Data Evaluation and Analysis

102 papers were reviewed and analyzed to identify similarities and differences between them and the stated review purpose. Twelve papers were excluded at different screening levels after screening and selection (Figure 1). Only 4 papers were included following good quality evaluation, which was evaluated by an accredited and approved tool (Johns Hopkins), and all papers were at level III (B) [8].

Descriptive statistics (percentages calculations) were used to analyze the three quantitative articles. The content analysis was used to analyze the qualitative paper. Primary coding was conducted, identifying patterns and connecting categories were identified, followed by theme searching and naming. The approach gave a researcher a deeper understanding of the phenomenon through the identified themes, patterns, interpretations of the results, and generation of a report. The analyzed data were presented and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: The evidence Table of Studies Included in the Integrative Review.

|

Author (s), Year, and Country |

Purpose/Aim and Method |

Population, Sampling Strategy, & Sample size |

Data Collection Method and Measures |

Results |

Study Limitations |

Quality Rating |

|

Spates et al. (2020)

United States |

The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of gendered racism among Black women. Method: A qualitative Exploration

|

U.S. Born Black women. Snowball-sampling N = 22 |

In-depth semi-structured interviews Interview guide Demographic characteristic questionnaire

|

|

|

Level III Good quality |

|

Szymanski and Lewis (2016)

United States |

The aim of this study was to examine how engagement and disengagement for coping with discrimination might explain how gendered racism influences psychological distress among African American Women Method: |

Female first-year college students (98% African American/Black; 2% Biracial) Convenience -sampling N = 212 |

Online survey Racialized Sexual Harassment Scale (RSHS) (α= 0.89) Coping with Discrimination Scale (CDS) (α= 0.72) In-Group Identification Scale (IGIS) (α= 0.76) |

|

|

Level III Good quality |

|

Thomas et al (2008)

United States |

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship of the accumulative effect of gendered racism, the discrimination felt by African American women on psychological distress. Quantitative, non-experimental descriptive correlational-cross-sectional |

African American women

Convenience-sampling

N = 344 |

Symptom checklist 90 (SCL-90) (α=8.0) Africultural Copying Styles Inventory (ACSI) α=0.76-0.82) Schedule of Sexist Events -Revised (RSSE) (α=0.93)

|

|

|

Level III Good quality |

|

Williams and Lewis (2019)

United States |

The purpose of this study was to explore the relations between gendered racial microaggressions, gendered racial identity, coping, and depressive symptoms among Black women. Method: Quantitative, non-experimental cross-sectional |

Black women

Purposive Sampling N =231 |

Online Survey Gendered Racial Microaggressions Scale (GRMS) (α=0.92) Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI) (α=0.64 for private regard and 0.87 for public regard) Brief Coping with Problems Experienced Inventory-(Brief COPE) (α=0 .75 for spirituality,0.88 for social support, 0.72 for engagement, and 0.71 for disengagement) Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) (α=0.88 for depression,0.82 for anxiety, and 0.83 for stress) |

|

Almost all the women came from a higher socioeconomic background and had a higher level of education (limited generalizability). Participants' socioeconomic backgrounds and education should be diverse. The MIBI scale did not capture all variables, so it was recommended to construct a new scale. Finally, the brief COPE scale was not specific to Black Americans, indicating the need for the development of an intersectional coping measures scale. |

Level III Good quality |

Results

Four (4) papers that met the inclusion criteria and an integrative review question were included in the review. Study characteristics included the following. All articles were conducted in the United States, ranging from 2008 to 2020 publication years. Three studies (75 %) used cross-sectional descriptive designs with sample sizes ranging from 212 to 344 [9,10, 11], while one study (25 %) used a qualitative approach with 22 respondents [12].

Convenience [9,10] and purposive [11] sampling techniques were used in a quantitative while snowball was used in a qualitative study [12]. For further information on the characteristics of the articles, see Table 1.

Study results were analyzed and synthesized to answer the research question. Three themes were identified across the studies, as described below. Out of the 3 themes, the first 2 themes could answer our research question across all the articles. The third theme focuses on coping strategies and the available support system to promote gender equality [9,10,11,12].

The Magnitude and Prevalence of Gender Inequality on Black Women

While the 4 studies included, all occurred in the United States. The findings do reveal how gender inequality does impact Black women more than White women [9,10,11,12]. Gender racism can be defined as how race and gender-constructed systems of oppression work together to create diverse burdens on Black women [3]. Across the 4 reviewed papers, gendered racism was more significant in African American women than in other races [9,10,12]. Gendered racism was found to be a chronic problem among African American women. Participants experienced a 71.8 % prevalence of discrimination and sexual harassment [10]. Moreover, [10] reported multiple sources of gendered racism: 91.3 % of gendered racism occurs in service provision, and 90 % occurs among helping professionals Table 1. One study (25 %) reported that societal and African American men believe the most important jobs for African American women are to carry out family chores [12].

Impact of Gender Inequality on Black Women's Psychological Well-being

All reviewed papers (100 %) reported the association between gender inequality and psychological effects among participants [9,10,11,12]. [12] stated that 73 % of participants experienced stress as the significant negative psychological impact of gendered racism. Fifty-five percent (55 %) of participants reported difficulties navigating relationships with friends, families, significant others, and romantic relationships. In contrast, 46 % reported difficulties gaining access to resources, jobs, and payments, which hurts their current and future personal and family lives [12]. Emotional distress [9], psychological distress [10], and depressive disorders [11] were also reported as outcomes.

The Coping Strategies and Available Support System

Psychological effects lead participants to adopt different coping mechanisms, which are thought to work well in reducing the problem. Most participants used disengagement strategies (detachment and internalization) as a coping mechanism against discrimination [9,11,12]. The disengagement coping mechanism increases psychological depression and other mental-related health problems. This is associated with decreased emotional support from significant others and decreased internalization of discriminatory processes [9,11,12]. Social support at different levels is critical to breaking gendered racism [9,10,12].

Intersectionality Framework

The intersectionality framework was identified as a key in exploring the experience of gender inequality-gendered racism by fifty percent (50 %) of the articles [9,10]. Gendered racism interconnects with other aspects (class, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and other identity markers), creating overlapping and interdependent discrimination systems. This analytical framework will assist in conceptualizing the social problem (gendered inequality and psychological well-being) and considering the participant's overlapping social, political, and experiences to understand the complexity of biases and formulate better strategies for intervening in the problem.

Discussion

A Synthesis of the Findings from the Literature

This paper sought to determine how perceived gender inequality in young women (ages 18 to 25 years) affects a sense of psychological well-being and, as such, may predispose them to a higher level of depression, anxiety, and poor coping mechanisms. The reviewed results provide a holistic understanding of the magnitude and gap of the problem globally and serve as a foundation for future studies in different geographical settings. The review shows limitations in the geographical representation of the findings since all (100 %) of the reviewed papers were limited to the United States. Due to the limited number of studies on this topic, the author increases the search range for papers to the past 16 years (i.e., 2007 to 2022). Studies were conducted in 2008, 2016, 2019, and 2020 respectively. Findings from this integrative review are presented in Table 1.

Gender inequality was reported in all papers as a global social and political problem with a higher prevalence in the United States among African American women [9,10,11,12]. However, we don’t have a comparative study conducted outside the U.S.; this shows that more studies are required across other countries to generalize and compare the magnitude of the problem globally. The quality level of the evidence of all four studies was determined to be Level III, good quality using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model and Guidelines [8].

A more vital link exists between gendered racism and specific contexts [10]. Discrimination is committed in different places (e.g., homes, workplaces, etc.) and by different people [10]. Discrimination was more common among service providers (91.3 %) and strangers (90 %), making no place safer for African American women [10]. The increased prevalence might be associated with a lack of strict laws and policies to protect the victims and punish the offenders. This shows that multiple efforts are needed to transform the negative per-perceptions of convicts toward African American women and promote a conducive and safe working environment for them. The review's findings align with those of Crenshaw, who reported gender racism as a problem associated with the intersecting identities of African American women with poor support from different levels [3].

All articles expressed psychological distress as the primary outcome of discrimination among participants [9,10,11,12]. This means the problem is catastrophic and needs to be addressed to improve the psychological well-being of participants and eliminate the mental problems associated with it. Poor coping mechanisms were noted by 75 % of the reviewed papers as the predisposing factors to mental health problems like stress and depression [9,10,12]. [12] reported multiple sources of psychological distress. Researchers reported that 55 % of participants who experienced psychological distress were associated with difficulties in engaging in relationships and marriages due to societal perceptions placed on them [12].

Moreover, 46 % of participants had trouble accessing resources, jobs, and employment. This might be related to the governmental systems and policies that do not provide equal opportunity. Multifaceted supportive approaches from governments, stakeholders, and the community must ensure diversity, equity, and inclusion prevail across people (Black/White or Women/Men). Similar findings were reported by Crenshaw, who expressed how the intersectionality of gender, race, and many others can increase psychological distress among African American women due to discrimination committed against them in different settings, which reduces their rights to opportunities and rights [3].

Seventy-five percent of reviewed articles reported that almost all participants used a disengagement approach in fighting against discrimination, either by staying at home or by withdrawing from people or events associated with gendered racism [9,11,12]. This copying mechanism (disengagement) has had adverse outcomes because, as the victims withdraw from others and themselves more, they push themselves towards psychological distress and mental-related conditions such as depression. A joint strategy between people involved in the practice, social issues, and research is required to develop the best coping mechanisms that promote positive psychological well-being among participants.

Applying the intersectionality framework is highly recommended [9,11]. The finding is consistent with that of Crenshaw (2016), who reported using the Intersectionality Framework in addressing gendered racism against African American women at different levels [3].

The Strength and Limitations of the Review

Strength of the Review

The integrative review question was comprehensive, clear, focused, and comprised all the critical phenomena. The introduction was broad and sufficiently explored, with a clearly stated problem of the statement and the purpose of conducting an integrative review. On methodology, the review was guided by Whittemore and Kanfl's five stages (Whittemore and Kanfl, 2005). The following methodological approaches were followed: (a) a summary table of the literature search and data evaluation. Bibliographic databases were appropriately identified and comprehensive. Three databases were used to search; keyword and inclusion criteria to guide the search were identified. A PRISMA-type flow chart was presented and clearly described. The John’s Hopkins guide was used to measure the excellence of the papers, which increased the study's rigor, and the data was presented in a summary table. (b) results: The procedures for producing results were done appropriately after Whittemore and Kanfl's guidance and presented in a well-organized way with adequate comprehensive information, and (c) presentation: data interpretations were performed, and recommendations were given. Author guidelines have been followed in preparing the manuscript.

Limitations of the Review

This integrative review was conducted, and one reviewer performed a synthesis. Future review advice should have a librarian and an anonymous review to avoid bias. The papers for this review were all from the U.S. since no studies were conducted in other countries. This made researchers include papers published more than 10 years ago (from 2007 to 2022). Moreover, only one paper was searched using the MeSH search items; the other papers were from the references of other papers. This limitation calls for further studies outside the U.S. to understand the diversity of the problem and strategies for approaching it. The findings cannot represent the world on global issues because, as we discussed above, all four papers included in this review were conducted in the U.S., reducing generalizability.

Review Applications in Practice and Future Directions

The Intersectionality Framework is suggested to be utilized by clinicians to assist in obtaining a clear awareness of clients overlapping collective characters and their experiences of discrimination [11]. Moreover, clinicians must support clients in selecting the coping mechanism that decreases the gendered racial psychological link [9]. Psychologists must be involved in providing treatment and counseling [9,10]. Psychological treatment support from the federal government for clients with psychological distress is strongly recommended [11].

Qualitative methodology is encouraged to assimilate rich and complex information from participants by exploring the nature and pervasiveness of gendered racism, its effect on mental health functioning and identity growth, and identifying the moderating and mediating variables and coping mechanisms [10]. Purposive sampling is encouraged [12]. Heterogeneous community-based samples from different socioeconomic backgrounds and education levels are encouraged to increase the generalizability of the findings [11,12]. On top of that, researchers employ an Intersectionality Framework to investigate participants' perceptions of gendered racial identity centrality [9]. An intersectional coping measure should be developed to capture more information for quantitative research [9,11]. Moreover, the Gendered Racial Microaggressions Scale is preferred to assess gendered racism, and the General Identity Centrality Scale evaluates intersections of gendered racism [9]. Social coping strategies are encouraged to promote gender equality and increase a positive sense of psychological well-being at various levels and settings (family, community (schools, churches, workplaces, etc.). This can be accomplished by increasing community understanding of gendered racism and creating different approaches for everyone to face up to the stereotype of gendered racism [12]. Moreover, the federal state needs to address the existing macro and microstructures to reduce the impact of gendered racism [12].

Conclusions and Implications

Gender inequality is a global problem that impacts Black women more than White women in the United States. The scope of the problem is diverse across settings (homes, workplaces, and many others). The negative impact of the problem causes psychological distress among participants. Poor coping mechanisms (disengagements) were reported to worsen the situation as they increased psychological problems. The Intersectionality Framework is highly recommended for practice and research in exploring perceived gendered racism by participants. Clinicians and psychologists are encouraged to intervene in gendered racism by evaluating the psychological effects of the problem and assisting clients with positive coping mechanisms. Stakeholders should focus on a coordinated mutual effort to reduce gendered racism while advocating for diversity, equity, and inclusion in different settings globally to improve the psychological health of African American Black women.

Acknowledgment

I am thankful to Almighty God through my Pastors in Tanzania, and in the United States (Dr. Huruma & Joyce Nkone, and Chris & Jan Beard) for their prayers and guidance. Special appreciation goes to my dissertation Chair (Dr. Carolyn Smith) who worked very hard in accomplishing this work, the University of Cincinnati College of Nursing for financial support, and the Hubert Kairuki Memorial University for granting permission to pursue my studies in the United States. Last, I am grateful to my husband (Remigius Modest Mawenya), my children (Glory and Josh Remigius), my sister (Neema K. Ngabeki and her family), my guardian (Professor Joseph Mlay and his family), and my mentor (Professor Amos Rogers Mwakigonja and his family) for their moral support.

References

- Arnett JJ (2007) Emerging Adulthood: What Is It, and What Is It Good For? Child Development Perspectives. 1(2): 68-73.

- Galambos NL, Barker ET, Krahn HJ (2006) Depression, self-esteem, and anger in emerging adulthood: seven-year trajectories. Developmental psychology. 42(2): 350–365.

- Crenshaw KW (2016) Demarginalising the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of anti-discrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and anti-racist politics. Framing Intersectionality: Debates on a Multi-Faceted Concept in Gender Studies. 1989(1): 25–42.

- European Commission (2004) Toolkit on Mainstreaming Gender Equality in EC Development Cooperation: Section 1: Handbook on concepts and methods for mainstreaming gender. European communities.

- Boston YW (2022) What is intersectionality, and what does it have to do with me?

- Bell S, Lee C (2008) Transitions in emerging adulthood and stress among young Australian women. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 15(4): 280–288.

- Halfon N, Forrest CB, Lerner RM, Faustman EM (2017) Handbook of life course health development. Handbook of Life Course Health Development. 1–664.

- Dang D, Dearholt S, Bissett K, Ascenzi J, Whalen M (2022) Johns Hopkins evidence-based practice for nurses and healthcare pro- fessionals: model and guidelines - full-text link below.

- Szymanski DM, Lewis JA (2016) Gendered racism, coping, identity centrality, and African American college women’s psychological distress. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 40(2): 229-243.

- Thomas AJ, Witherspoon KM, Speight SL (2008) Gendered racism, psychological distress, and coping styles of African Ameri- can women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 14(4): 307-14.

- Williams MG, Lewis JA (2019) Gendered racial microaggressions and depressive symptoms among Black Women: A moderated mediation model. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 43(3): 368–380.

- Spates K, Evans N, James TA, Martinez K (2020) Gendered racism in the lives of Black women: A qualitative exploration. Journal of Black Psychology. 46(8): 583–606.