Gudeta Didi1, Murtii Teressa Obolu2*, Tadesse Getachew4, Ermias Tadesse4

1MD, Consultant Pediatric Surgeon, Assistant Professor of surgery, Department of Surgery, Ethiopian Minister of Health, Worabe Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Worabe, Ethiopia

2MD, Senior Resident, Chief General Surgery Resident, Department of Surgery College of Medicine & Health Science, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia

3MD, Senior Resident in General Surgery Department of Surgery College of Medicine & Health Science, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia

4MD, Senior Resident in General Surgery, Department of Surgery College of Medicine & Health Science Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia

*Corresponding Author: Murtii Teressa Obolu, MD, Senior Resident, Chief General Surgery Resident, Department of Surgery College of Medicine & Health Science, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia.

Abstract

Background

The term ‘delayed infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis’ generally refers presentation of the disease beyond 6th weeks of infant life. Delayed Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is very rare 1 in 100,000 as described in different literature. Classically infants presented with non-bilious vomiting from 3rd to 5th weeks of age. Particularly presentation beyond five month is extremely rare clinical condition. Non the less, Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis caused by hyperplasia of pyloric smooth muscle result in gastric outlet obstruction. Which is the most common cause of non-bilious vomiting in infants. Mainly first-born male predominance, approximately 1-4 per 1000 live births. However, there are a few cases are reported in literature with median age of 08- month-old and as let as 17-years-old on delayed presentation of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis leads to diagnostic dilemmas and delay management.

Case presentations

This article reports on a case of delayed infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a first-born male who was 09 months old baby. Presented with frequent non-bilious projectile vomiting of ingested matter together with a substantial amount of unquantifiable body waste, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, later diagnosed with delayed infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and managed surgically.

Results

At first, the baby was diagnosed with SAM, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, and delayed infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. After achieving the best possible preoperative care and stabilization, the patient underwent laparotomy a standard open Ramstedt's pyloromyotomy and post operatively satisfactory outcome.

Conclusion

Hence, infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis doesn't always appear in a classic age of life, Pediatric patients exhibit persistent projectile, non- bilious vomiting of ingested matter, severe associated body waste should be evaluated inline of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and early correction of fluid and electrolyte derangement and surgical intervention is crucial.

Keywords: Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, pyloromyotomy, Gastric outlet obstruction, Paradoxical aciduria

Introduction

Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis caused by hyperplasia of pyloric smooth muscle fiber of pylorus, leading to elongation and wall thickening result in pyloric luminal narrowing by a redundant pyloric mucosal tissue causing gastric outlet obstruction. Which is known to be the most common cause of surgical vomiting in infants. Classically infants presented with non-bilious projectile vomiting particularly the child get hunger after vomiting & suck breast well. Dehydrated and wasted. Usually from the period of 3rd to 5th weeks of age. Mainly first-born male predominance, approximately 1-4 per 1000 live births. However, delayed Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is very rare 1 in 100,000 as described in different literature. the term ‘delayed infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis’ generally refers to the presentation of the disease beyond 6th weeks of infant life, there are a few cases are reported in the literature with a median age of eight months and as let as 17 years of age on delayed presentation of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis which result in diagnostic dilemmas and delayed management.

Diagnosis is thorough clinical history and examination for atypical presentation and definitive diagnosis can be made with abdominal ultrasound which has high specificity and sensitivity and rarely contrast meal and other modalities are needed.

Here in this case, we are reporting a 09-month-old male infant diagnosed with SAM, electrolyte imbalance, delayed infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and successfully managed with open standard Ramtsedt pyloromyotomy and satisfactory outcomes on subsequent follow ups.

Case presentations

This is a nine-month-old male infant presented with persistent projectile vomiting of ingested matter of 3 weeks. That the baby feeds well after vomiting associated with significant but unquantified weight loss. He was born from 25 years old leady after amenorrhoea of 09 month. uneventful spontaneous vaginal delivery of active baby with birth weight of 3.5kg. Whom was on exclusive breast feeding for the first six month and started weaning with homemade mixed gruel just two months back, for this compliant he was taken to multiple health facilities had given unspecified per os syrup medication and advice on gruel modification on local hospital but finally referred for no improvement seen.

On physical examination baby was severely wasted body, weighted 4.7kg and dehydrated, he was irritable, tachycardic, tachypnic but had no fever record. He was able to maintain saturation without oxygen support and no palpable mass appreciated on abdominal examination but epigastric was full and fast capillary filling, sunken eyeball, slow skin turgor and he is lethargic

The baby was investigated with serum electrolyte (Na+-132mE/L, K+-2.7mE/L, Cl-- 87mE/L) blood count (wbc-11.83 thousand, Neu- 41.9, hgb-10.1g/dl, PLT-328 thousand) abdominal ultrasound was done and pyloric wall thickening of 378mm and 189mm channel length with high likely suggestion of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (Figure 1) and contrast study was not available in our setup to investigate further for clearing of diagnostic dilemma.

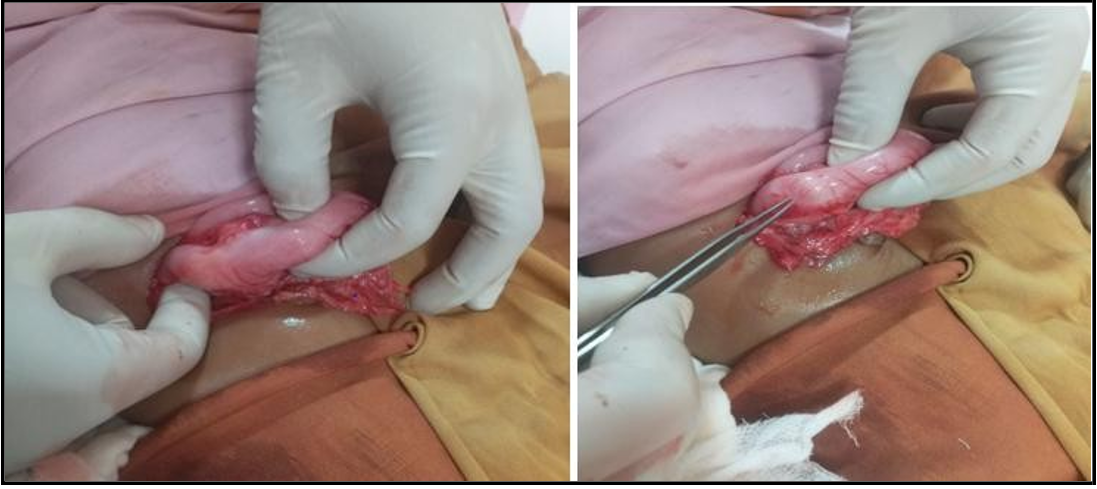

Patient was stabilized and optimized with normalized electrolyte and out of dehydration. Informed written consent was taken from family and under general anaesthesia, through right upper quadrant transverse incision, thickened pylorus delivered to wound, with longitudinal serosal incision and blunt splitting of thickened pylorus smooth muscle, pylorus mucosa bulged completely without intraoperative incident and abdomen closed in layers (figure 2&3). Post operatively patient was discharged on second post operative day as vomiting subsided and infant tolerated breast feeding well. On subsequent follow up after two weeks baby’s weight increased to 7.3kg and well looking alert baby.

Figure 1: abdominal ultrasound illustrating pyloric smooth muscle thickinned378mm and elongated 189mm and collapsed lumen

Figure 2: intraoperative photograph of thickened pylorus indicated between fingers of surgeon and scalpel

Figure 3: intaoperative photograph of divided thickened pylorus muscle and bulged mucosa indicated between fingers of surgeon and scalpel

Discussion

Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis has been known since Hirschsprung's time causing most common surgical vomiting in children from obstruction of gastric outlet. There are several worldwide studies and literature done on the disease etiology implicating genetic, hormonal and environmental as risk factors in all age groups. But no exactly known cause identified yet [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. The disease pathology is progressive. However, it is not well established how long it will take for symptoms to appear. But the average duration described in different literature is (1-10) weeks usually begins at 4 weeks. The thickness and elongation of the pyloric wall is crucial for diagnosis. The primary pathology is hypertrophy and typical hyperplasia of the pyloric smooth muscle fiber, lead to redundant pyloric mucosa causes further luminal narrowing. Eventually result in pyloric obstruction that hinders emptying of gastric content antegrade and further retention of content with continuous peristalsis of stomach against obstructed pylorus induce vomiting of ingested matter together with electrolyte result in significant emaciation & electrolyte imbalance [2, 6, 7].

The classic presentation of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is classically observed between the third and fifth week of life. During this time, the infant may experience progressive non-bilious projectile vomiting of ingested matter, which is accompanied by hunger feed and severe wasting and dehydration. This was reported from different case report and research article that this classic presentation is noticed almost more than 90% of patients [8, 9].

According to a few case reports in the literature, the majority of cases involve people who are older than five months or who are as old as seventeen years [3, 6]. In our case, we are reporting the diagnosis of IHPS in a 09-month-old. Delayed IHPS is a rare clinical entity with similar clinical features that is overlooked primarily due to atypical age of presentation.

The primary clinical and non-invasive imaging methods for diagnosing infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is ultrasound.

These methods have become standard in patients with classic presentations at typical ages with high diagnostic accuracy and sensitivities, even though some presentations are atypical or even recurrent. Thus, we must further investigate with upper gastrointestinal contrast meals, endoscopies, or CT scans to have a clear differentiation from possibly existing differential diagnosis.

When a patient presents with the classic presentation, the most important diagnostic evidence is the clinical evidence of progressive non-bilious vomiting of ingested matter. Usually associated with body waste, dehydration, even shock, severe acute malnutrition. often a palpable olive mass on the epigastric area under calm conditions. This is supported by laboratory findings of hypokalaemic hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis and ultrasound confirmation of pyloric thickness of >=3-4mm and elongation of >=14-16mm in term infants. Abdominal ultrasonography in this case demonstrated a 189 mm long and 378 mm thick pyloric wall, and clinical data corroborated our conclusion that final surgical intervention was necessary [10, 11, 12].

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment even though there is a place of medical treatment options. Since the disease known there are different surgical techniques applied for IHPS management in different literatures. However, Ramstedt's pyloromyotomy is the standard procedure with excellent outcome for a century. Here in our case, we applied the same standard technique, and it was successful with satisfactory outcome patient relieved symptom on subsequent follow up [8, 13, 14, 15].

Conclusion

Hence, infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis doesn't always appear in a classic age of life, Pediatric patients exhibit persistent projectile, non-bilious vomiting of ingested matter, severe associated body waste should be evaluated inline of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and early correction of fluid and electrolyte derangement and surgical intervention is crucial.

Authors’ contributions

Gudeta Didi- Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation

MurtiiTeressa Obolu- Conceptualization, Writing original draft, review edition, software

Tadesse Getachew Mulisa- Investigation and data curation

Ermias Tadesse-Data curation and Software

Informed consent

Patient family has provided written informed consent for the publication and the patient's name has been anonymised for privacy; a copy of the consent is available for distribution to the chief editorial of this case study.

Funding: No financing.

Disclosure of Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest in computation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the patient’s family for providing us with informed consent for publications.

References

- Iacoviello O, Verriello G, Castellaneta S, Palladino S, Wong M, et al. (2022) Case report: Late-onset hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a 3-year-old boy: It is never too late. Frontiers in paediatrics. 10: 949144.

- Bartlett E.S, Carlisle E.M, Mak G.Z (2018) Gastric outlet obstruction in a 12-year-old male. Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports. 31: 57–59.

- Fadista J, Skotte L, Geller F, Bybjerg-Grauholm J, Gørtz S, et al. (2019) Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies BARX1 and EML4-MTA3 as new loci associated with infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Human Molecular Genetics. 28(2): 332–340.

- Abdellatif M, Ghozy S, Kamel M.G, Elawady S.S, Ghorab M.M.E, et al. (2019) Association between exposure to macrolides and the development of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Pediatrics. 178(3): 301–314.

- Ranells J.D, Carver J.D, Kirby R.S (2011) Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Epidemiology, genetics, and clinical update. Advances in Pediatrics. 58(1): 195–206.

- Chalya P.L, Manyama M, Kayange N.M, Mabula J.B, Massenga A (2015) Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis at a tertiary care hospital in Tanzania: A surgical experience with 102 patients over a 5-year period. BMC Research Notes. 8: 690.

- Peeters B.C.M, Benninga M.A (2012) Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis—Genetics and syndromes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 9(11): 646–660.

- Mahalik R.K, Prasad A, Sinha A (2013) Delayed presentation of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A rare case. Journal of Clinical Neonatology. 2(3): 146–148.

- Ndongo R, Tolefac P.N, Tambo F.F.M, Abanda M.H, Ngowe M.N, et al. (2018) Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A 4- year experience from two tertiary care centres in Cameroon. BMC Research Notes. 11(1): 33.

- Nazir Z, Arshad M (2005) Late-onset primary gastric outlet obstruction—An unusual cause of growth retardation. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 40(6): e13-6.

- Bajpai M, Singh A, Panda S.S, Chand K, Rafey A.R (2013) Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in an older child: A rare presentation with successful standard surgical management. BMJ Case Rep. 2013: bcr2013201834.

- Hernanz-Schulman M (2003) Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Radiology. 227(2): 319–331.

- Akbulut S, Yagmur Y (2010) Late-onset hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Definition of diagnostic criteria and algorithm for the management. World Journal of Gastroenterology 16(1): 1–4.

- Selzer D, Croffie J, Breckler F, Rescorla F (2009) Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in an adolescent. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 19(3): 451-2.

- Ogunlesi T.A, Kuponiyi O.T, Nwokoro C.C, Ogundele I.O, Abe G.F, et al. (2016) Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with unusual presentations in Sagamu, Nigeria: A case report and review of the literature. The Pan African Medical Journal. 24: 114.